Patent Information

With Frequently Asked Questions

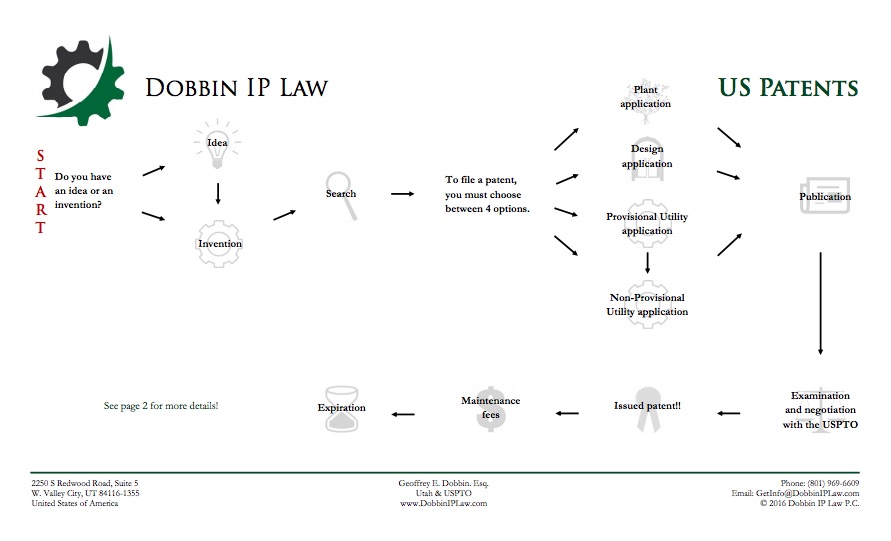

You have invented... something.

It may be the newest kitchen or household gadget, a new method of manufacturing a product, a new process, anything. Either way, it will change the world for the better; but, what do you do with it now? At Dobbin IP Law, we can help you protect your invention.

We secure patents so that only you may control it for years to come. With even the most complex inventions and industries, we pick technology up quickly so as to provide you with the highest quality legal service possible. We work closely with our clients so we can provide the best representation possible.

A patent is a property right often referred to as a "limited monopoly." It is designed to give inventors the right to exclude others from using, manufacturing, and selling their inventions in a given country. Before receiving a patent, inventors must disclose the process by which their invention is made and how it works. As a part of the bargain, after a patent expires, the invention is released into public domain for all to use and improve.

There are three types of patents:

Utility Patents

A utility patent is the most common type. A patent in this category is based on the processes or machines by which the invention operates. Manufacturing improvements also fit into this category. The object or process that is described must be new, non-obvious and useful. Most utility patents last between 17-20 years.

Design Patents

A design patent focuses primarily on the appearance and ornamental design of the item being patented. These last 15 years.

Plant Patents

A plant patent is issued to those who have discovered new varieties of plants through the process of asexual reproduction. They last 20 years from the date of filing the application.

As one of the first steps in applying for a patent, you must decide if you want a provisional application or a non-provisional application. Whichever you decide upon, you will eventually need to file a non-provisional. However, many opt to start with the provisional application. In doing this, not only is the upfront cost lowered, but the words "patent pending" can be used on the product even as you continue to develop your invention before proceeding to the more final filing of the non-provisional patent application.

Subsequently, you will need to decide whether or not to use a patent attorney. Our experience shows that many inventors can file a basic provisional patent application on their own; however, in doing so most risk not disclosing enough in the specification to support a patent. Also, in many cases, the time taken to draft a provisional application by yourself is usually measured in multiples over what a patent attorney would take, simply because we, as a whole, have done this many times before. Thus the results are faster and more complete. In any event, when the time comes to file the non-provisional application, it is highly beneficial to have an experienced attorney who knows how to work with the United States Patent & Trademark Office and how to meet all standards while making your patent as strong and broad as possible.

The Search

Since a patent is granted based on improvements an invention makes over the state of the art then known (the "prior art"), it is generally a good idea to examine the prior art to first determine if the invention appears patentable and that the invention does not infringe someone else's patent. We provide both patentability and freedom to operate opinions to help with your due diligence.

Contact an Experienced Patent Attorney

If you have any additional questions regarding patents, please review our Patent FAQs section below, containing answers to many commonly asked questions. Additionally, you can call to schedule your complementary strategy session where we can discuss the particulars of your invention and how we can help you.

At Dobbin IP Law, we pride ourselves in being as honest and upfront with our clients as possible. So we will let you know as soon as possible whether or not we think your invention is patentable.

Our Patent Work

Dobbin IP Law has secured patents in a wide range of technical fields. Below are some examples of our patent portfolio.

No patent data available. Please try refreshing the page.